“I was very close to this city, but at the same time, very alienated from the society.”

Hsieh Tehching1

At 2 p.m. on September 26, 1981, Taiwanese-American artist and illegal immigrant, Hsieh Tehching began his new series One Year Performance, also known as Outdoor Piece, at Tribeca Park, Manhattan. In this new piece, Hsieh declared that he would stay outdoors for a year; his written statement, signed by himself and witnessed by friends, claimed that Hsieh would not “go into a building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, tent.” With this statement, a shaved-head, a rucksack equipped with some maps of New York City, a sleeping bag, a camera, a torch, a radio, and a nunchaku, he walked out of his studio and (Fig.1) entered the streets of downtown Manhattan. By walking the streets and embracing the unknown contingencies that lay before him, Hsieh could began to map the city.

Each day, Hsieh land-surveyed lower Manhattan and recorded his routes and daily activities on to a mapping sheet he designed. He recorded the piece title, duration, and his hybrid name Sam Hsieh (a cover for his illegal status) on the upper margin, while the date was included on the lower left. Another mapping sheet included a map of lower Manhattan, and the one with the uptown Among the 381 sheets, most of them are Hsieh’s itineraries in downtown area, such as Tribeca, China town, and Bowery. Everyday, Hsieh would leave different traces on the map, sometimes he would circle out a territory. Other times there were simple straight lines following the grid system of Manhattan. For example, on Thursday, January 28, 1982, he recorded that he had breakfast at W. 21 St. at 9:10 a.m., made a fire at 7:40 a.m., and spent a certain amount of money that day. Every day, he used the leaking water from any broken fire hydrant to wash his face and brush teeth. He bought meals from food stands on the streets and slept in parking lots,outside abandoned factories, or under a tree. He mingled with the crowds, buying clothes in the outdoor flea market ; His daily life was in accordance with different parts of Manhattan, parts that are rarely noticed by other residences in New York City.

Fig 1. Installation view from "Doing Time", Image from Hugo Glendinning.

In his previous one-year performances, Cage Piece and Time Clock Piece, Hsieh masters the exploration of inhuman conditions. He forces himself to experience rigorous situations considered by some critics to be his recollection of bodily memories that were ingrained while he carried out his compulsive military service in Taiwan. Hsieh’s life in Taiwan has not been fully discussed by art historian Adrain Heathfield, who has written the most comprehensive study of Hsieh’s performance thus far in the book entitled, Out of Now: The Lifeworks of Hsieh Tehching. Adrian Heathfield claims that Hsieh’s long-durational, self-restricted performance pieces are characterized by their “durational affects” or “durational aesthetics,”2 and that this order of temporarily is what sets Hsieh apart from other body artists. Heathfield argues,

“Hsieh’s course away from an aesthetic of explicit risk, from painful testing of bodily limits characteristic of his earlier performances and common in a range of contemporaneous Body Art practices, can be seen as one which seeks to move beyond the frame of the rupturing event, the traumatic instance of performance, and into another order of temporality: duration. Here the testing of corporeal limits is turned more extensively toward the practice of living, it existential nature and ethical dilemmas.”3

Therefore, Heathfield is convinced that Hsieh Tehching is an artist who masters time. Time is Hsieh’s artistic medium and by these self-alienated durations and physical challenges, his life and art are seamlessly correlated to each other; His life equals his art, that is, his lifeworks. This unseparated condition is like the pair of fish described by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, “they are glued together, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures; or even like those pairs of fish (shark I think, according to Michelet) which navigate in convoy, as though united by an eternal coitus.”4

It is a bit spooky when Barthes’ description of the mechanic character of photograph perfectly fits with the unseparated situation between art and life in Hsieh’s performances. The possible connection between self-ruled body, machinery and pain is further explored in Gong Jow-jion’s article “Critique, Translation and Abstract machine: A Study on the Critiques of Tehching Hsieh’s work.” As the Chinese translator of Out of Now, Gong takes Heathfield’s formal interpretation of Hsieh’s works and durational aesthetics a step further to consider an abstract, durational machinery in Hsieh’s performances. Gong views Hsieh himself as a restricted time measuring machine. In Time Clock Piece, the artist ties himself to a punching card machine, compulsively punching it every hour for a year. Gong compares this performance to the killing machine in Franz Kafka’s short story “In the Penal Colony.”5 By viewing Outdoor Piece as an appendix to Time Clock, Gong is convinced that Hsieh extends his needles into the city.6

Both of Heathfield and Gong attempt to find an overarching argument, one term, or concept in Hsieh’s lifeworks that could encompass all of his durational performances. Even though Heathfield almost achieves a monopoly in the discourses around Hsieh, Out of Now is claimed as a long-durational co-creation between Heathfield and the artist. Outdoor Piece is the only lifework that leaves Heathfield speechless. “I was finding it is hard to write on this environmental work, so remote from my own experience.”7 Outdoor Piece is too slippery to fit into Heathfield’s concept of “durational aesthetic” and leaves him no choice but to re-enact Hsieh’s wandering in the city.

Heathfield’s re-performance of Outdoor Piece both demonstrates the problematic of Outdoor Piece and romanticizes. Yet the obscurity for Heathfield is that this durational piece lacks the punctuality demonstrated in Hsieh’s previous works. Although it has self-imposed rules and restrictions, it does not share the cruelty or harshness of “the killing machine,” as Gong implies. Rather, it is playful and high-flying. As the artist once light-heartedly describes, “In Outdoor Piece, I expanded my activity to treat the whole city as my home. For instance, Chinatown was my kitchen; the Hudson river was my bedroom; those parking lots, empty swimming pools, and small parks were my bedroom. In winter, the Meat Market West of 14th Street was my fireplace.”8 His self-imposed restrictions on living outdoors for a year were almost seems like a Huck-Finn-style American adventure.

To discuss Outdoor Piece, which, in many ways, differs from Hsieh’s previous performances, I purpose a new reading. Rather than a time-constructed work, Outdoor Piece is more like a space-oriented performance. By performing this nomadic way of living, living outdoor for a year and not entering any modernized, manmade institutions, Hsieh Tehching demonstrates creative lines of flight away from his sedentary experiences in Taiwan while also setting himself apart from the reenactments of this inactivity in his previous one-year performances, created while he had illegal status in the states: Cage Piece and Time Clock Piece. Furthermore, we can also sense two paradoxical frameworks enmeshed in this year-long process of mobilization. On the one hand, there are specific, self-restricted rules and disciplines and on the other, these limitations lead him to a liberation through an itinerant way of living. This freedom allows him to survive under the radar of state apparatuses and further obscures the socially constructed boundaries between private and public spaces. Additionally, Outdoor Piece should be considered both as a temporal duration and a spatial extension performance. The following discussion is an attempt to map out Hsieh’s transition from sedentary to mobilization and from oppression to emancipation.

I. Hsieh’s Double Escape and His Military Body Memory

In Outdoor Piece, Hsieh walked out of his apartment bareheaded. It was the third time Hsieh began his performance with this ritual. For his previous One Year Performance series, Cage Piece and Time O’clock Piece (Fig.2), Hsieh began his works with a shaved head and a custom uniform that had his name embroidered and a series of numbers on his left chest. In each work, the rules might be slightly different, yet Hsieh always carried out self-imposed and stoic rules for his own appearance. This was an attempt to reach both the physical and mental limits. In art historian Frazer Ward’s article entitled, “Alien Duration: Tehching Hsieh, 1978-1999,” Ward argues that as an illegal immigrant in the U.S. and a performance artist who uses his own body as the medium, Hsieh expresses a diligent denunciation of subjectivity in his performance. He suggests that “Hsieh’s near-systematic negation of subjectivity, staking out a position along the intersecting limits of economic, juridical, and political orders, in the end gives rise to a counterintuitive and critical inversion to sovereignty.”9 With this gesture of emancipation in mind, Ward also asks what Hsieh was like and why he would want to put himself through these rigid situations. However, by purposing that these deviated behaviors were initiated from Hsieh’s alien status in the states, Ward only partially answers his own inquiries. The parts that he leaves unresolved are best formulated into questions; what was Hsieh like before he illegally entered the U.S.? From what kind of subjectivity did Hsieh wish to divorce? And why does Hsieh inaugurate his performance with a shaved head? In order to answer these questions, and see why Hsieh must mobilize himself to cross borders, we should look back to his life in Taiwan.

Fig 2. Installation view from "Doing Time", Image from Hugo Glendinning.

In his interview with Heathfield, Hsieh explains what urged him to leave Taiwan. He says it was the isolated and “oppressive atmosphere”10 that alienated him from the exciting avant-garde art of the western world. This oppressive atmosphere was not limited to the art world but pervasive in Taiwanese society and politics overall. It was certainly not the first time for Hsieh to experience the shaved head in his first piece of One-Year Performance in 1978, and so did these elements of technique apparatuses, such as “inaugural declaration, long-live durations, under self-imposed constraints, legalistic apparatus of proof, mechanisms of surveillance, refusal of a specific orders of representation and senses.”11 as listed and described by Heathfield. As a Taiwanese child born in 1950 under the military dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek government, Hsieh was molded by these disciplinary frameworks that were physically and mentally pervasive throughout his youth.

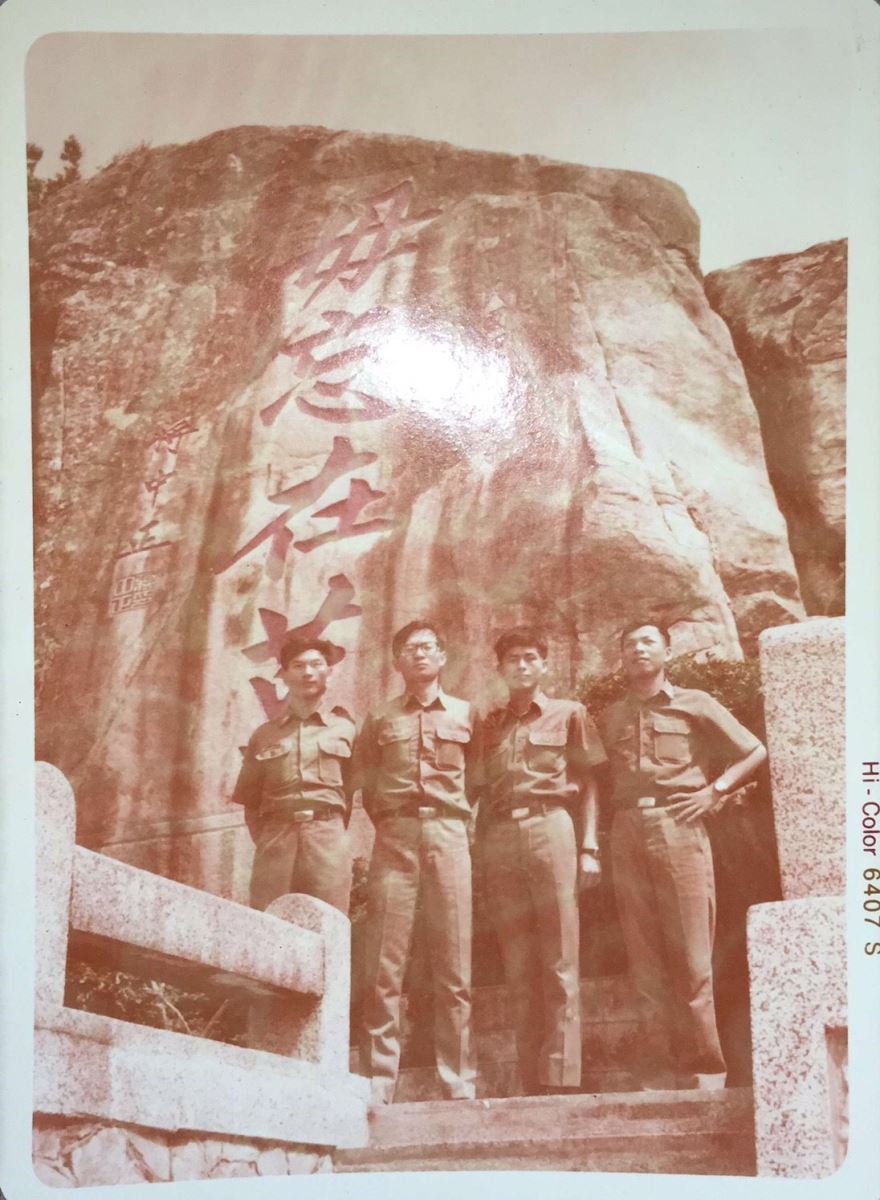

Hsieh’s adolescence and his young adult life run parallel to the restricted socialized militarization conducted by KMT.12 It is not a coincidence that Hsieh’s disciplined body required for Cage Piece and Time Clock Piece, share an affinity to the disciplining of male bodies in Taiwan beginning at a young age. If we compare the photo-document of Hsieh’s performance and the military group portrait of my father, taken in the camp at Kinmen County, the front line between the KMT and Communist Party in China, it is clear that both young males share specific characteristics. (Fig.3) They both wear uniforms, stand with their body erect, and sport newly grown hair or none at all. Their body postures are reminiscent of the unrequited dream of the KMT, and emblematic of the productive and disciplined bodies that the KMT desires. Additionally, high school life is partially constructed as preparation for militarized education and discipline later on. According to the policy of the Education Department in 1962, “all schools shall apply military management since the very beginning of school orientation, in order to establish an understanding of the military discipline, and allow students to be accustomed to it for the safety of our country.”13 Every detail of school life must follows the rules of the military: étiquette, customs, appearances, and punishments. Together, by creating a possible threat: the possibility of Communist invading Taiwan, KMT government successfully achieves its socialized militarization to secure its governance over the Taiwanese.14

Fig 3. A piece of photograph taken at a time when my father was serving his compulsive military service in Kinmen.Image from the author.

In that sense, Hsieh’s look: bareheaded, dressed in a uniform with an embroidered name and number, and military posture are body memories embedded in a Taiwanese young male born and raised under martial law (1949-1987). In addition, the years-long isolated experience that they have to endure during their compulsory military service is also echoed in his performances. It is not a surprise that right after three years of de-characterized training, Hsieh stopped painting.15 However, from his last two paintings, Military ID and Paint.Red Repetitions, both constructed in 1973, the military memories are salient. In Military ID, Hsieh horizontally divides the white canvas into two parts, and paints in the typical colors in school, military camps or other disciplinary fields, white and green. The picture plain stands like institutionalized wall, and Hsieh writes down his military ID numbers on it. Similar to other Taiwanese males, his identity is entwined with indifferent, non-characterized numbers. Soon after Hsieh gave up painting, as if he wished to disassociate with his sedentary, militarized body, he began to conduct body performance pieces. In Jump Piece (1973), one of his early performances in Taiwan, Hsieh jumped from a second-floor window onto a concrete floor. This fifteen-feet jump broke both of his ankles and continues to be painful.16 Almost like a suicidal act, this was a real jump with no photomontage nor cushions on the ground; yet, this jump, in the price of discomforting his body, mobilizes himself to be a disfavored body of the KMT government.17 A year later, Hsieh decided to become a seaman and this time he jumped off a boat onto the land of New World.

Some Taiwanese artists living in Taiwan such as Lee Ming-sheng (1952-) and Chen Chieh-jen (1960-), created performance works that resonate with Hsieh’s works.18 While Lee and Chen’s performances are still governed by the military dictatorship in the early 80s, their performance works centered on the body speak to a political commitment not seen in Hsieh’s works. In his Malfunction, No.3, Chen compares the martial-law body to the ancient and uncivilized punishment to the prisoners.19 With their heads covered with black clothes, five young males demonstrated the panelized bodies under the oppressive political atmosphere. Chen’s performance ended with a long and painful screaming as if there was no way out. Simultaneously, these shouts were calling up for resistance. These disturbing and traumatic experiences should not be cushioned under the image of prosperous Taiwan.

While his contemporaries in Taiwan were demonstrating their oppressive bodies, Hsieh’s demonstrates the loosening grip of these oppressive bodily memories in Outdoor Piece. As he opens the door of his apartment and commits himself to exploring the streets of lower Manhattan, Hsieh’s previous body memories are erased. Unlike his previous works, where Hsieh wore embroidered uniforms, the traces of the military body are gone. All the past that remains is Hsieh with a shaved head. Instead of a disciplined soldier though, Hsieh looks more like someone recently discharged from the army, ready to embrace and encounter a city life full of changes encounters and circumstances. He wears a causal shirt, jeans, and a giant rucksack.20 He switched his body from self-imposed isolation to total exploration, from a secluded cage to a metropolitan city.

The gesture of opening the door is a second escape for Hsieh Tehching. Through door-opening, the signification between indoor and outdoor, private and public is about to be reverse and even opaque. We can consider his illegal trip from Taiwan to the U.S as the first. The changes of both Hsieh’s physical appearances, such as growing his hair, threadbare clothing, and homelessness look, are not simply a “corporeal index of time,”21 but are statements of a nomadic liberation. Through physically surveying New York City, a place Hsieh enters illegally, the artist destroys his original identity and nationality and performs a great escape by mapping out the lower part of Manhattan.

II. A Nomad in the City

“If I had any thought at all, it was to let chance determine what happened, to follow the path of impulse and arbitrary events.”22 The monologue from Marco Stanley Fogg, the protagonist in Paul Auster’s novel, Moon Palace, gives us a possible glimpse of Hsieh’s mental activities when he was performing Outdoor Piece. The artist does not say much about how he chose his paths or what he encountered every day in his grand tour. Nevertheless, he left hundreds of documented maps, photographs, and a fifty-minute video filmed by his friend, Robert Attanacio,23 for us to reconstruct or visualize his grand tour through New York City. In each of Hsieh’s documented maps, he meticulously records dates, temperatures, daily activities, expenses, and circles his territories with a red pen. Taking a closer look at these maps, it is clear that these records are done in a succinct manner, as if Hsieh was once again a seaman, on a journey from Taiwan to the U.S., and using these maps as his Pacific journals.

Hsieh’s explorations are reduced to the document of basic human needs. He records when he eats, sleeps, and defecates. If we look at these time marks, we might fall into the same conclusions that Gong made: That Hsieh is a scrupulous time measurer and that “the body of the artist becomes a needle of a clock, and is writing around the city of Manhattan and its suburb.”24 For Gong, these time markers are Hsieh’s check points this Hsieh still functions as a restricted machine even though he has been released from the cage. However, since he breaks through the self-isolation in a cage or ties to a time clock in exchange for going outdoors, Hsieh’s measurements go beyond time to a specific space — a metropolis that changes every second. From the photographs and the video clip, Hsieh is seen as oftentimes mingling with the crowds. He buys food from street venders, argues with a seller in a flea market, and makes a fire with the homeless. He occupies the desolate spaces in the city-parking lots, empty pools, abandoned factories, and parks. During his performance of Cage Piece, Hsieh divides the four corners of the cage into different spaces. His bed is his “home” and the other three corners in his cage are parks. As a result, every morning Hsieh would walk from his imagery home to the out-side parks.25 In other words, these imaginary spaces served as a mental prison break. The cage, both a signified institutionalized public surveillance and artistically-delineated private room, is further divided to another private and public space between home and park again. This mise-en-abyme of distinctions between“public” and “private” is reenact in Outdoor Piece, and this time Hsieh attempts to map the whole city as his home.

In that sense, Outdoor Piece is not simply a sequence from the previous durational aesthetic piece as both Heathfield and Gong assert, it is rather a work about space and dismantling of locational identity. When he escapes from his self-built cage, a gesture of liberation from the previous oppressive body memory, Hsieh joins the dérive. A term coined by Guy Debord, the derive “entails playful constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects.”26 Like the Situationists, Hsieh, initiates topographical experiments that tie to the revolution of everyday life.27 In other words, Hsieh begins “cognitive mapping”28 to delineate the city and to relocate the impasses on the map which, in turn, open up the possibility of lines of flight.29 The intriguing case of Heathfield’s doubling of Hsieh’s Outdoor Piece demonstrates the affinity between this piece and the Dérive. Comparing the re-performance of Heathfield to George Maciunas’ Free Flux-Tour (1976), the idea of city as a playground or adventure site are both contextualized in both case — a free for all tour to rediscover and reclaim the institutions and identities provides in New York City. Nevertheless, Heathfield’s remapping lacks the whimsical practices of everyday life or sprightly exploration in to the unknown city as we have seen in Maciunas’ tours. Nor did Heathfield share the lighthearted claim that Hsieh makes about viewing Manhattan as his home. “As a re-doing of a tiny fragment of Hsieh’s work, my walk starts as a hopeless tourism and closes as a failed attempt.”30 By tracing Hsieh’s map, literally taking the same routes that the artist has taken decades ago, Heathfield’s re-performance is stratified due to his romanticized empathy and structural existentialism. When distinguishing a map from tracing, Deleuze and Guattari argue, “The tracing has already translated the map into an image; it has already transformed the rhizome into roots and radicles.” The lack of critical point might lie in the fact that Heathfield forgot that a map should always has multiple entries “The map is open and connectable in all of its dimensions; it is detachable, reversible, susceptible to constant modification”31 The randomness and flexibility that Hsieh creates through his everyday routes is a making of animal rhizome.32 The contingencies that Heathfield sacrifices are where Hsieh’s lines of flight as passageways emerge.

In this space-orientated work, his itinerary is different from the sophisticated and refined grand journey shared by the bourgeois in their leisure hours. It directly follows his basic needs: eat, drink, sleep, and keep warm. Hsieh leads a nomadic life in order to open the passageways as lines of flight. The photographs show Hsieh falling asleep between cars in parking lots, making fires under the bridge, and taking a bath besides the bank of the Hudson River. He claimed his territories among the spaces deserted by the bourgeois and in hybrid areas occupied by different immigrants and all walks of life, such as China town or the Bowery. From his documented maps, we see that he rarely went uptown and the only place he visited there was Central Park.33 The reason is, perhaps, provided by Macro Stanley Fogg once again, “There is no question that the park did me a world of good…the grass and trees are democratic, and as I loafed in the sunshine of a late afternoon, or climbed among rocks in the early evening to look for a place to sleep, I felt that I was blending into the environment.”34

In Outdoor Piece, Hsieh’s paths are directed by his essential demands and his territories are the unclaimed regions that have long been forgotten by society. Hsieh lives a nomadic life as Deleuze and Guattari proposed,

“The nomad has a territory; he follows customary paths; he goes from one point to another; he is not ignorant of points (water points, dwelling points, assembly points, etc.) . But the question is what in nomad life is a principle and what is only a consequence. To begin with, although the points determine paths, they are strictly subordinated to the paths they determine, the reverse happens with the sedentary. The water point is reached only in order to be left behind; every point is a relay and exists only as a relay. A path is always between two points, but the in-between has taken on all the consistency and enjoys both an autonomy and a direction of its own. The life of the nomad is the intermezzo.”35

Take the documented map of December 8, 1989, for example. Hsieh’s territory is marked by four different points: he wakes up at an empty swimming pool, defecates at Greenwich St., buys lunch and dinner at 190 Heater St, and sleeps at 96 Greene St. These four points circle part of Soho and the Bowery. These two areas still have unclaimed spaces that were illegally occupied by artists groups as well as nomads like Hsieh. This nomadism is argued by Deleuze and Gauttari as “a way of life that exists outside of the organizational State. The nomadic way of life is characterized by movement across space which exists in sharp contrast to the rigid and static boundaries of the State.”36 In that sense, Hsieh follows the nomadic life based on his basic needs as an artist and a human; he searchs for a new water point where life for an artist is more democratic. In 1974, Hsieh jumped from the boat to destroy his former identity in Taiwan and became an illegal immigrant in the U.S. Unwanted and unrecognized by both governments, his double renouncements, or the negation of subjectivity as suggested by Frazer Ward,37 inevitably leads Hsieh to a nomadic life, a life that dismantles the control of the States and a fixed identity.

Furthermore, in Outdoor Piece, this micro-version of Hsieh’s nomadism demonstrates a gesture of deterritorialization. The double denial of his subjectivity and agency are both retained. During this overlapping of art time and real time, Hsieh chooses to live outdoor for a year — a year of nomadic life as an art, which is acknowledged by law in the previous legal charge. Yet, Hsieh might not need the jurisdiction from the judge to reterritorialize his subjectivity and agency. Once you live like a nomad, you receive the support from the earth. Therefore, Hsieh’s saying that he expands the activity to treat the whole city as his home resonates with Deleuze and Guattrai’s arguments,

“With the nomad, on the contrary, it is deterritorialization that constitutes the relation to the earth, to such a degree that the nomad reterritorializes on deterritorialization itself. It is the earth that deterritorializes itself, in a way that provides the nomad with a territory. The land ceases to be land, tending to become simply ground (sol) or support. The earth does not become deterritorialized in its global and relative movement, but at specific locations, at the spot where the forest recedes, or where the steppe and the desert advance.”38

In other words, if Hsieh is a nomad in the city, then Hsieh is reterritorialized by his bodily extension and redefinition of public and private space: the Meat market, Hudson River, and Central Park, places where the power of institutionalization are vulnerable and ambivalent.

Following Deleuze and Gauttari’s rhizomatic nomadism, Outdoor Piece, in a broader sense, is in accordance with art historian, Miwon Kwon’s concept of the mobilization of site-specific art. In describing these reiterated, itinerated site-specific artworks, such as Mark Dion’s On Tropical Nature (1991) or Christian Philipp Muiller’s Illegal Border Crossing between Austria and Czechoslovakia (1993), Kwon purposes that “Rather than resisting mobilization, these artists are attempting to reinvent site specificity as a nomadic practice.”39 These nomadic practices, she further argues, continue to shatter and loosen the fixed, rigid placed-bound identities, and substitute them with “the fluidity of a migratory model, introducing the possibilities for the production of multiple identities, allegiance, and meanings, based not on normative conformities but on the nonrational convergences forged by chance encounters and circumstances.”40 It is, perhaps, this argument that the nomadism of Hsieh can be understood. His demand to live outdoors and the random choice of these deserted spaces blurs the social-constructed boundaries between public and private spaces while also denouncing that subjectivity multiplies numerous identities. It is now clear that what Hsieh means when he says, “I was very close to this city, but at the same time, very alienated from society.”

Therefore, Outdoor Piece is never a performance that is only concerned with temporality. The meticulously documented maps show that the marks cannot be regarded as one place after another, but, as Kwon implies in mobilized site-specific arts, rather they are as “one person, one thought, one fragment next to another.”41 Instead of a proof of continuity, or a certification of the existence of the eventually ephemeral performance, these almost identical maps and the numerous correspondences between Hsieh and the artists from various parts of the world should also be regarded as spatial, geographical extensions, and as his attempts to cross more borders. Each mark and postcard are scattered fragments, where the meanings of each site never unfold in a timely sequence but in collisions. Seen from Hsieh’s routes in lower Manhattan, one can describe, but never categorize; They are whimsical and contingent, filled with chance encounters and unpredictability — The Hudson River could be a bathroom and a porch as a bed.

Toward the end of Hsieh’s journey, the photographs show Hsieh waking up. We can imagine that his photographer friend woke him up by saying, “Good morning, Sam.” Hsieh opened his eyes, sits up on the porch, which was his bed last night. His hair is long, a bit disheveled, and some of his hair stubbornly sticks out. He sits casually with his left leg up on the porch. His casual posture was decidedly different from his military life in Taiwan: erect body, eyes to the front, hands at his side, and heels together. Now, he looks like a discharged soldier, living for another day to search territories.

III. Conclusion: Hsieh’s final jump

During his art life = real life, Hsieh performed three jumps or, more precisely, three mobilizations: the first is his Jump Piece (1973), which he performed soon after being discharged from the army, the second was his jump from the ship that carried him from Taiwan to Philadelphia, and the third was Outdoor Piece. In each jump, he attempted to extricate himself from an unwanted restriction or domineering political atmosphere. In each jump there were also productions of psychogeographic maps. In his first jump, from a second floor window, Hsieh broke both of his ankles. This self-inflicted pain is reminiscent of what young Taiwanese males would do to avoid being enlisted in the military. They would destroy their own bodies to free themselves from two years of isolation and the healthy and productive body that the KMT government desired. However, Hsieh choose to damage his body after completing his service. This leap unfolds two layers of a post-disciplined body in Taiwan. On the one hand, it seems like a leap, an outcry from the conservative art atmosphere in Taiwan that Hsieh wishes to escape. On the other hand, it is a jump from a collective memory shared by Hsieh and his contemporaries. The militarized society leaves them no choice but to jump, to protest with a broken body. Thus, Hsieh’s leap must be an authentic jump. It could not be a photomontage leap posited by Yves Klein. After all, it is the gravity that matters, which inevitably draws Hsieh to the concrete ground, and has caused him pain ever since.

Hsieh’s second jump took place in 1974 when he decided to become a seaman and planed his great escape to the exciting New York City. This genius pursuit could only be possible by sabotaging his nationality and destroying his identity. At the same time, this leap freed him from a sedentary mode. To be a mobilized subject, Hsieh must renounce his real name and become neither Taiwanese nor American. Hsieh declares himself as a nomad with a hybrid name, Sam Hsieh, who jumps the boat and for another water port that will fertilize his art.

In his third jump, Outdoor Piece, Hsieh leaps from his self-isolated cage towards the city. He begins his nomadic life through the modernized metropolitan city. By regulating himself outdoors, by not taking the bus or the subway and not entering any buildings, Hsieh regresses to an uncivilized man, or a painter of unmodernized life. A life without any sophisticated social rules and without divisions between work and leisure time. His needs and requirements return to a basic level: eat, sleep, and sometimes, protect yourself with a pair of nunchaku. He crawls between a nomadic life and the unclaimed territories of lower Manhattan, remapping New York City from these obsolete spaces.

Crystallizing these three mobilizations, Hsieh liberates himself from sedentary experiences and a fixed, given identity to a fluid, contingent subject. Outdoor Piece demonstrates the paradoxical nature that lies within Hsieh’s performance: the reenactment of the restricted body which was imposed upon with compulsive rules and standards during the postwar military dictatorship in Taiwan and the self-imposed outdoor orders. Hsieh lives like a nomad and the whole city is his cheerful, buoyant wonderland. Perhaps, these two convoluted forces in Hsieh’s performance widen the margin between geographical and political boundaries. His nomadic life could lead to an alternative narrative of modern progress that contrasts to the efficient, advanced society promised by the military state in postwar Taiwan, while also questioning the haunted cultural rebellion founded between the U.S. and his pacific allies as the phantom from the cold war. His body performance, photography documents, maps, and correspondences, show how Hsieh multiplies the previous dominated narrative of our temporal and spatial senses, and renders them disjunct.

In one of his photo documents, Hsieh Tehching stands outside the wall of a criminal court, underneath a frieze, with the inscription: “The only true principle of humanity is justice.” Hsieh looks directly at the camera, standing on the boundary between indoor and outdoor, between an instituted society and an open city. His figure is rather blurry and out of focus and the inscription stands fixed, clear, and steadfast like a giant wall. To our great relief, we know that Hsieh was standing outside of the court wall. This is Hsieh Tehching’s Outdoor Piece, and he has completed his performance with a perfect trajectory, a line of flight.