When did contemporary art first emerge in Southeast Asia? Recent art historical scholarship and exhibitions on art in Southeast Asia has gradually converged in the 1970s as the formative decades for contemporary art practices orbiting around the conceptual in art. These writings on contemporary art are produced as texts for exhibitions, and hence exhibitionary discourses that slip between art historical scholarship generated by the academia but intersects with the curatorial, and manifests in exhibitions that display many of these works discussed in these writings. Exhibitionary discourses form a distinct knowledge category as discursive site where the curatorial and art history meet.Telah Terbit (Out Now) Southeast Asian Contemporary Art Practices During the 1960s to 1980s with Ahmad Mashadi as the lead curator was organised as a Singapore Biennale special event in 2006 at the Singapore Art Museum. This landmark exhibition was conceived along two trajectories.

If these works are to provide a cursory snapshot of contemporary practices in Southeast Asia during the 1970s, then such practices on the one hand characterised two broad approaches; conceptualism and statement-making, and realism and forms of activism. However on the other, these need not be seen as mutually exclusive to one another, but rather trajectories with common contextual, historical, social and political groundings.1

Conceptualism and activism along the lines of the figural and statement-making (such as art manifestos) as modes of activism inhabit, fester and grow in shared historical, political and cultural contexts. Conceptualism as ideas, figuration, narrative and activism is expanded by art historian, T.K. Sabapathy in his exhibition, Intersecting Histories Contemporary Turns in Southeast Asian Art in 2012 at the ADM Gallery, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His exhibitionary text locates the conceptual turn as part of contemporary art practices cultivated in ‘employing media, material, technologies experimentally and extra-artistically, moving away from creating art that is seen aesthetically embodied in objects whose appeal is determined by visual properties and principles, to producing works whose constitution is variable, unstable and even unruly, and whose significance is ascertainable in relation to competing structures of power and value’.2 The notion of art itself is expanded across media and materials in an interdisciplinary manner. The following year, Iola Lenzi, a curator and art critic extends the notion of the conceptualism in her exhibition, Concept Context Contestation Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia in 2013 at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre. She connected Conceptual Art in Euroamerica with conceptualism in the region by stating:

That there are areas of intersection in the mechanics and characteristics of Conceptual art on one hand, and Southeast Asian conceptual strategies on the other, is certain, namely critical spirit, concern with the everyday, and interest in viewer perspective... Aestheticism, iconographies, vernacular techniques, and materiality, not obstacles to be spurned, act as repositories of meaning and beyond the descriptive to help deliver the concept, artists exploiting them as entry points for actively engaging audiences with ideas on collective issues.3

The everyday as a conceptualist strategy in Southeast Asia is identified as a shared concern with Euroamerican Conceptual Art in Lenzi’s view while acknowledging their differences. Conceptualism in Southeast Asia as asserted by her curatorial position in this exhibition alluded to conceptualism as ‘an expanded field’ that includes conceptual strategies that deploy not just ideas but also iconographies in painting, the materiality of objects, as well as local techniques and technologies to engage audiences critically to raise their awareness by heightening an understanding of their own social and political contexts grounded in everyday life. The idea of turning to the everyday in the context of Indonesia could be traced to the term turba, which means ‘going down below’ advanced by Lembaga Kedudaiyaan Rakyat (LEKRA) in Indonesia in the 1950s and early 1960s. In the late 1970s and 1980s, F.X. Harsono, one of the leading artists of the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (New Art Movement) proposed the term Seni Kontekstual (Contextual Art) and Seni Penyadaraan (Awareness Art) as a conceptualist strategy that draws on local materials imbued with culturally specific meanings to make art objects is markedly different from conceptualism in Euro-America. Moelyono developed the concept of Seni Penyadaran or the conscientisation art that focused on raising criticality of audiences by making visible and subverting dominant ideologies thereby breaking the cycle of socialisation that entrenches these oppressive regimes.4 Relating the everyday and the quotidian to conceptualism in the Philippines as a critique of commodification, ideology and the politics of identity argues for a turn to the everyday as the heartbeat of conceptualism. While Lenzi constructs a more unified notion of conceptualism in Southeast Asia, curator and art historian Isabel Ching alerts us to how conceptualism in the region itself springs from diverse well springs and motivations;

While the almost imperceptible early stirrings of conceptualism in Singapore tend to be associated with criticism of the painting medium, failure and repression, the displacement of retrograde criteria for beauty and skill, the resuscitation of the artistic function of intellectual engagement, and involvement with identity politics, amongst others, its beginnings in the Philippines are tied to a sense of the everyday, the valuing of process over form and style, anti-commodification, and art practices marked by an "unapologetic interiority," "wary of being subsumed by ideology and developmentalism," and "refus(ing) to tangle with questions of identity and origin"—what some perceive as a politically-alienated and elitist stance.5

What deserves further enquiry is to unpack the relationships between the everyday, conceptualism and exhibitions that function as vehicles that propelled the art historical wheels to turn not only to conceptual but to the everyday that is grounded in the realities, contexts, and politics of the region. The curation of conceptualism in Southeast Asia from Telah Terbit, Intersection Histories to Concept Context Contestation have proposed the conceptual as having set on a different art historical trajectory from Conceptual Art in Euroamerica. These exhibitions have demonstrated how it is impossible for conceptualism to be politically, socially and culturally removed. Conceptualism is also not only about ideas but how to activate these ideas to change mindsets and world views by generating critical thinking through provocations, engaging with the constellation of social and political issues that mattered using any materials and images that could be decoded by local audiences to effect change.

This paper argues for a turn to the everyday in Southeast Asian art in the 1970s by focusing on the birth of a new exhibitionary mode—the critical exhibition— that emerged and proliferated across Southeast Asia in the 1970s. More importantly, it traces the turn towards the everyday with new modes of representation in art discourse, materiality, and image-making as gears that turned the wheel of the everyday marking a conceptual shift propelled by critical exhibitions. It traces the exhibition histories of the region and locates the emergence of the critical exhibition out of the Cold War that resulted in student protest movements, rapid industrialisation, internationalism, and emerging nationalisms in the process of decolonisation in post-war Southeast Asia.

The critical exhibition marked a shift towards the conceptual, the assembly of everyday objects, the dissolution of the ‘white cube’ gallery into public spaces like streets, a desire for participatory and social engagement, and a consciousness of the need to explode Euroamerican notions and categories of art centred on a turn to the everyday. Critical exhibitions differed from previous types of exhibitions such as the salon, national, regional and internationalist-type exhibitions as earlier forms of modernist exhibitions primarily focused on displaying art as autonomous artworks detached from the realities of the outside world that does not come in. The title of this paper, ‘The descent to the everyday’, references Miyakawa Atsushi's influential text, 'Anti-art: Descent to the Everyday' (1964) that explains the shift towards the rupturing of barriers between art and everyday life when artists in Japan began to use junk and other non-art materials in their works in the 1960s. For Miyakawa:

“The descent to the everyday is nothing other than the annihilation of the border between art and non-art.”6 Anti-art was not non-art as it only sought to “recover a fundamental structure of the ‘actual’ world through everyday objects, signs and vulgar images...”7

It marked a contemporary turn that consistently seeks to abandon the detached realm of the modern artwork by descending to the reality of everyday life as an elusive goal that it can never attain. Walter Banjamin’s idea of ‘trash aesthetics’ as the use of everyday junk materials, the detritus of modern life to critically attend to what has been overlooked, hence avoiding a sentimentalisation of the past and elegising ‘progress’ and the new is useful in thinking about how artists in this region rematerialised non-art materials as art framed as a critique of what constitutes art itself.8 This paper argues that it was more than a shift to the conceptual that marked a decisive break with modern art in Southeast Asia but a ‘descent to the everyday’ manifested in the aesthetic discourse, materiality and modes of representation orbiting around the question of: what is the real.9

Ahmad Mashadi’s article that sought to reframe the changing artistic practices in 1970s Southeast Asia brings our attention to:

…the contexts of social and political transformation in the region within which developments in prevailing artistic practices and conventions took place. The tenor or intensity of such conditions varied across locations, yet they broadly informed the emergence of artistic discourses marked by newer attitudes towards the role of artists and art, as well as the constitution, the materiality of art, and the considered references made to society and notions of publicness.10

References to shifts in changing attitudes to the role of artists in society, public-ness, materiality and art’s constitution are important markers identified by Mashadi as he focused his attention on artistic practices in his article on ‘Reframing the 1970s’.

The turn to the everyday in the 1970s could be conceived as an ‘aesthetics of decolonisation’ that searched for alternative modes of representing the realities of the everyday A close examination of artworks displayed in critical exhibitions seek to make visible how a turn to the everyday within the context of Internationalism challenges the simplistic binary between realism focused on the figure and representation against conceptual practices and abstraction that mirrored the ideological struggle of the Cold War. Instead, a shift towards investigating the material of the everyday became the heartbeat of emerging conceptual practices that returned to local contexts and histories that intersected with the 3 trajectories of Internationalism: the Real, Abstraction and the conceptual.

This paper will foreground the turn to the everyday as a form of consciousness that manifested in critical exhibitions. A shared desire to attend to the realities of the everyday and generate new representational forms that counter and make visible the dominant social, cultural and political structures of the ‘real’ world that was itself changing translated into an’ aesthetics of decolonisation’ using the material of everyday life to foreground the world as a sensual and mental experience. The urgent need to register contemporaneity as a radical experience located at the level of everydayness makes the familiar unfamiliar to make visible social practices to transform daily life, reclaims public spaces for social change, and to raise the consciousness of the people to seek alternative ideas and models outside Euromerican systems of thought. Together, the critical exhibition attends to the everyday as moments of critique in the process of decolonisation that started in the 1970s as a process of defamiliarising the routine in everyday life as a form of resistance against the experience of modernity as routine, repetition, bureaucratic and capitalistic. The critical exhibition that embraced the everyday by making strange what otherwise goes unnoticed is transformed into a site for resistance to re-order power relations, and challenge fixed hierarchies as a vehicle in the process of decolonisation that intersects with new modes of representation. The critical exhibitions in the 1970s that this paper examines include: A Documentation of Experiences Initiated jointly by Redza Piyadasa and Suleiman Esain 1974 (Malaysia), the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (Indonesia) exhibition in 1975, and the Bill Board Cut Out exhibition by TAFT (Thailand) in 1976.

Articulating the Everyday: Aesthetics of Decolonisation in the Everyday

The modern in Southeast Asia was propelled by forms of abstraction and realism that engaged with broader international trends in the world. While abstraction embodied desires for ‘progress’ to replace previous conservatism, realism appealed to the depiction of present realities and conditions of the present for social change. Both abstraction and realism formed part of the larger international confluence of cultural debates shaped by Cold War ideologies captured in Claire Holt’s ‘Great Cultural Debate’ between the Bandung School labelled as ‘Laboratory of the West’ by Trisno Sumardjo, and the realists from Yogyajarta led by artists like S. Sudjojono who believed that art is the expression of Jiwa Ketok or the visible soul of the artist who inevitably expresses his or her national culture and emotions in their art.

While similar cultural debates occurred across the region in the 1960s, the institutionalisation of abstraction and realism began through the establishment of art societies organised by artists propagating abstraction and the universal such as the Modern Art Society, and Alpha Gallery in Singapore, Sang Tao (Creation Group) in Vietnam, the Gelanggang Group in Indonesia, and their opponents who gravitated towards realism like the Equator Art Society in Singapore, and Lembaga Kedudaiyaan Rakyat (LEKRA) in Indonesia and Kaisahan (Unity) in the Philippines. The Cultural Centre of the Philippines (CCP) established under by the Marcos regime, the Bhirasri Institute of Modern Art (BIMA) in Bangkok and the Taman Ismail Mazuki (TIM) in Jakarta are examples of art institutions built as sites where the pulse of internationalism could manifest in engagement with the national that also yearned for international recognition. These institutions provided spaces for experimental interdisciplinary practices, including modes of abstraction and other international art movements regarded as ‘progressive’ and therefore aligned with the authoritarian regimes that promoted ‘developmentalism’ to generate economic prosperity as an end in itself to justify the erosion of freedom and democracy. For example, the rhetoric of national unity and rising living standards accorded authoritarian regimes developmental legitimacy under Suharto’s New Order regime in Indonesia, Thanom Kittikachorn’s military rule in Thailand, and Fernando Marcos’ martial law in the Philippines. ‘Developmental art’ that was conceived as ‘progressive’ because it engaged with international art movements broadly in the three trajectories of conceptualism and abstraction was therefore supported by these authoritarian regimes to construct and project a democratic, liberal and open international face to the global community of nations, aimed primarily at the West.

Understanding the confluences of abstraction against realism in a period of intensifying internationalism runs the risk of constructing a simplistic binary opposition yoked to the logic of the Cold War. Abstraction was not necessarily conceived as ‘art for art’s sake’ that celebrated the unfettered autonomy of art uncritically detached from reality. Art critic and artist, Rodolfo Paras-Perez, argued that “the one constant factor in this stylistically protean scene lies in the concerted move from illusionistic realism towards actual reality— a stress… on pigments and gestures in painting rather than the subject or theme.”11 Painting the modern in the Philippines remained grounded in reality while negating the illusionistic impulses of realism. The notion of reality itself was claimed by both realism and gestural paintings with sympathies with Art Informel and other forms of abstraction. The question of what is the real’ becomes a contested terrain that cannot be separated from the notion of everyday life and its realities that artists whatever their ideological or artistic inclinations. What was at stake was the representational mode, whether abstraction, plasticity or illusionistic realism most suited to depicting the realities of the everyday.

Realism as the representational mode was advocated by the Kaisahan as a way to depict the everyday life of the Filipino people and also seeks to change their lives by uplifting it through art, clearly articulated in their art manifesto:

But we wish to gradually transform our art that has a form understandable to the masses and a content that is relevant to their life… We shall therefore develop an art that not only depicts the life of the Filipino people but also seeks to uplift their condition. We shall develop an art that enables them to see the essence, the patterns behind the scattered phenomena and experience of our times. We shall develop an art that shows the unity of their interests and thus leads them to unite.12

The Kaisahan sought to make visible the otherwise invisible patterns of everyday life through Realism as a mode of representation that is transmissible to the ‘masses’ to awaken their consciousness and unite them for action. They were not alone. The Artists Front of Thailand (TAFT) grew out of the larger student movement that successfully demonstrated against and brought about a change in government in Thailand. The establishment of the Thammasat University, a product of the 1932 revolution led by the People’s Party adopted an open admission policy that opened up the opportunity for a university education to all Thais regardless of their economic background unlike the Chualalongkorn University that catered largely to the elite. Post war Thammasat University became a hotbed for student activism with students from different economic classes, including the working class spearheading anti-imperialist protests against Japan led by Pridi Banomyong from the Free Thai movement. Unlike other universities in Thailand that shifted emphasis to hard sciences as dictated by the military regime, Thammasat University focused on expanding its humanities and social sciences from which many of the student protestors came from. The student movements in Thailand and Indonesia shared a belief in their privileged status as a moral force above the corruption of their governments. They sailed on the powerful potential of youth shaped by ideas perpetuated by the New Left to transform society by challenging the institutions of the regimes that propped up the authoritarian capitalist and developmental regimes that they were trying to reform or change. TAFT produced an art manifesto along similar lines to the Kaisahan declaring that:

The Artist Front of Thailand’s promotion on the valuable culture art could help the “little people” develop their ethnicity (value of living and social, intellectual, and moral thoughts) to fight the injustice in society. All in all, to develop the whole Nation and society, the basics of life, i.e., politics, economics, education, and culture art must be correctly and relatively promoted.13

TAFT’s call for the ‘basics of life’ was a return to the everyday and its structures in the social, political, economic, education and art. It is the structures and conditions of the everyday that needs to be changed from the ‘bottom-up’ and art was seen to be play and empowering role for social change.

In 1974, members of the Group of Five in Yogyakarta (Indonesia) were involved in a dispute between the students and the ASRI administration, culminating in what is now known as the ‘Black December Affair’. The Black December Manifesto was issued in reaction to the jury’s decision that favoured works by the more established artists such as Widayat, Abas Alibasyah and AD Pirous at the 1974 Grand Exhibition of Indonesian Painting. The Manifesto proclaimed the following:

1. Diversity is undeniable in Indonesian art, even if diversity does not by itself signify a desirable development.

2. For the sake of a development that ensures the sustainability of our culture, it is the artist’s calling to offer a spiritual direction based on humanitarian values and oriented towards social, cultural and economic realities.

3. Artists should pursue various creative ways in which to arrive at new perspectives in Indonesian painting.

4. Thereby, Indonesian art may achieve a positive identity.

5. Obstacles in the development of Indonesian art come from outdated concepts retained by the Establishment by art business agents as well as established artists. To save our art, it is now time for us to pay tribute to the established by giving them the title of ‘cultural veterans’.14

Fourteen artists, including FX Harsono signed the document, issued as a response to the perceived favouritism and conservatism of the judges of the 1974 Grand Exhibition of Indonesian Painting favouring decorative paintings that was judged by established artists. The protesting artists sent a wreath on the day when the announcement of the five winners were made. The wreath read: ‘Our condolences upon the death of the art of painting’. The five winners who were Widayat, Irsam, Aming Prayitno, Abad Alibasyah and AD Pirous. The protest by the fourteen artist-students could be seen within the context of the broader student movement in 1974 that peaked with the Malari Incident that manifested the discontent of students against government institutions, including art academies that appeared to exhibit any form of corruption including favouritism and conservatism the parameters of what art could be. Like the larger student movement, the fourteen artists who issued the Black December manifesto were seeking to reform ASRI and its perceived conservatism.

The Manifesto was welcomed in Jakarta and Bandung with the exception of ASRI, which suspended ASRI’s students who signed it.

Just eight months after the Black December Affair, the Group of Five and other artists from Bandung, together with noted art critic and lecturer Sanento Yuliman established the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (GRSB) and organised an exhibition in August 1975 at Ismail Marzuki Art Centre, Jakarta (TIM). Works presented in this exhibition were socially engaged, raising issues concerning injustices beyond the field of art to include socio-economic and political issues, aligned with the Black December Manifesto that called for artists to develop socially engaged artistic practices. Works shown by the GRSB artists included a wide range of art forms such as installation art that questioned the definition of art circumscribed by the aesthetic conventions and practice of painting. The use of everyday materials to make artworks expanded the restricted use of what was considered art materials as oil and watercolour paints to found objects that embody local symbolic cultural and political meanings.

The contestation over the ‘real’ in the everyday and how it was to be represented took a different articulation in Indonesia over the ‘maya’ (illusory world) and the concrete. Art critic Sanento Yuliman explained this in relation to his defence of the artists and artworks of the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (GSRB) critical exhibition, and is worth closer scrutiny:

Jim Supangkat went further by not producing anything at all. He simply asked someone else. In the New Art Movement 1975 exhibition, forms and qualities conventionally attributed to a work of art, in whole or in parts, were not produced by the artists themselves, but rather assigned to carpenters, puppet makers or plastic and aluminum manufacturers. … In response to the notion of 'real' and the 'maya' (illusory world), these artists proposed the use of concrete objects [readymades]. …

Can we say from this exhibition that we are being introduced to an aesthetic experience that is new where the ‘sense of concreteness’ becomes the basis to that same experience, hence transforming the experience qualitatively into one that is ‘conventional’, as though to shock us with the materiality [emphasis added] of the banal?

Earlier generations of artists were satisfied with works that were bound by the imaginative experience and reflections into an inner realm. Artists participating in this exhibition step out of these constraints, aggressively moving into the 'outside realm'[emphasis added], the concrete world, as if aiming that art can provide an experience which is full and total.15

The representation of the ‘concrete world’ using ‘concrete objects’ found in everyday life is proposed as a ‘new aesthetic experience’, a ‘sense of concreteness’ to shock the viewer using concrete objects that are banal everyday materials as opposed to the illusory world drawn from the artist’s inner realm. Concreteness as a shift from the interior imaginations of the artist to the exterior concrete materiality of the banal such as crates and cushions that we are familiar with in everyday life, are now transformed into artworks. The aggressive shifting of these concrete artworks into the ‘outside realm’, the world of the everyday was to manifest in the materiality of art.

Re-materialisation of the Everyday

The use of everyday non-art materials to make artworks expanded the restricted use of what was considered art materials as oil and watercolour paints to found objects and even readymades that embody local symbolic cultural and political meanings. Iola Lenzi postulates the critical potentialities of re-contextualising these local materials while differentiating it from neo-traditionalism and essentialism:

Some indigenous materials, signs and techniques, including the hand-made (paper, ceramics, wood-block printing, woven rattan, wood carving, textile) close to village or folk culture, are employed not for their nostalgic connotations of pre-modern life, but because even once re-configured and re-contextualised, their rules of application modified or forgotten, they yield additional layers of information, idiomatic bridges facilitating the mediation of challenging content.16

FX Harsono, one of the leading artists of the GSRB proposed the term Seni Kontekstual (Contextual Art)17 and Seni Rupa Penyadaran (Creating Awareness or ‘Conscientisation Art’) as a conceptualist strategy that draws on local materials imbued with culturally specific meanings to make art objects is markedly different from conceptualism in Euro-America. The notion of Contextual Art is connected to a literary movement that occurred simultaneously - Contextual Literature (Sastra Kontekstual in Bahasa Indonesia) - that sought to foster a socially engaged literary discourse to challenge the formal structuralist and universal humanist literary discourses that were manifestations of depoliticised literary production in Indonesia and across the rest of Southeast Asia. American art critic Lucy Lippard introduced the term ‘dematerialisation’ in conceptual art in 1967 as a reduction of material in art making to reduce art to its purest form such that it would only exist as an ethereal concept. The dematerialisation of art was a rejection of the material construction of art for the conceptual production and dissemination of ideas, a dominant conceptualist movement from 1966 to 1972 in Euro-America. Dematerialisation of art did not occur in the conceptual in Indonesia. Instead, it re-materialised everyday objects by making strange and defamiliarizing them from their usual contexts and functions, and reassembling new meanings that reveal the hidden structures of power and control over the rakyat or people.

Enceng Gondok (fig1) by Siti Adiyati that was shown in the 1975 GSRB exhibition was the only work that used a living organism, the enceng gondok, a type of water hyacinth, and an invasive species originally from the Amazon basin now commonly found in the region. Amidst the water hyacinth are plastic golden roses to contrast between life and artifice to provoke audiences to think about the delicate balance in the relationship between humans and nature. Bringing a living organism into the GSRB exhibition also collapses the bridges the gap between art and non-art and recontextualises both the water hyacinth as a kind of floating aquatic plant and a weed due to its high reproduction rate caused by agricultural waste polluting rivers and lakes by raising its nutrient levels commonly found in Indonesian villages that could destroy aquatic life. Siti recontextualises the water hyacinth as a potentially environmentally harmful weed and the plastic golden roses by revealing that Suharto’s New Order that purported developmentalism ‘is just an illusion symbolised by the golden rose) in the sea of absolute poverty that the enceng gondok represents. This is why the enceng gondok is included in the art movement (GSRB). That is my point to understand everyday life’.18 Siti’s approach to use the real problems and issues of everyday life through the water hyacinth that is recontextualised from both a harmful weed embedded with potentialities to also be useful that is never realised within the current social and political structures created by the New Order.

Fig.1

Siti Adiyati

Enceng Gondok

Plastic, water hyacinth

1979

Collection of Artist

Image from the author

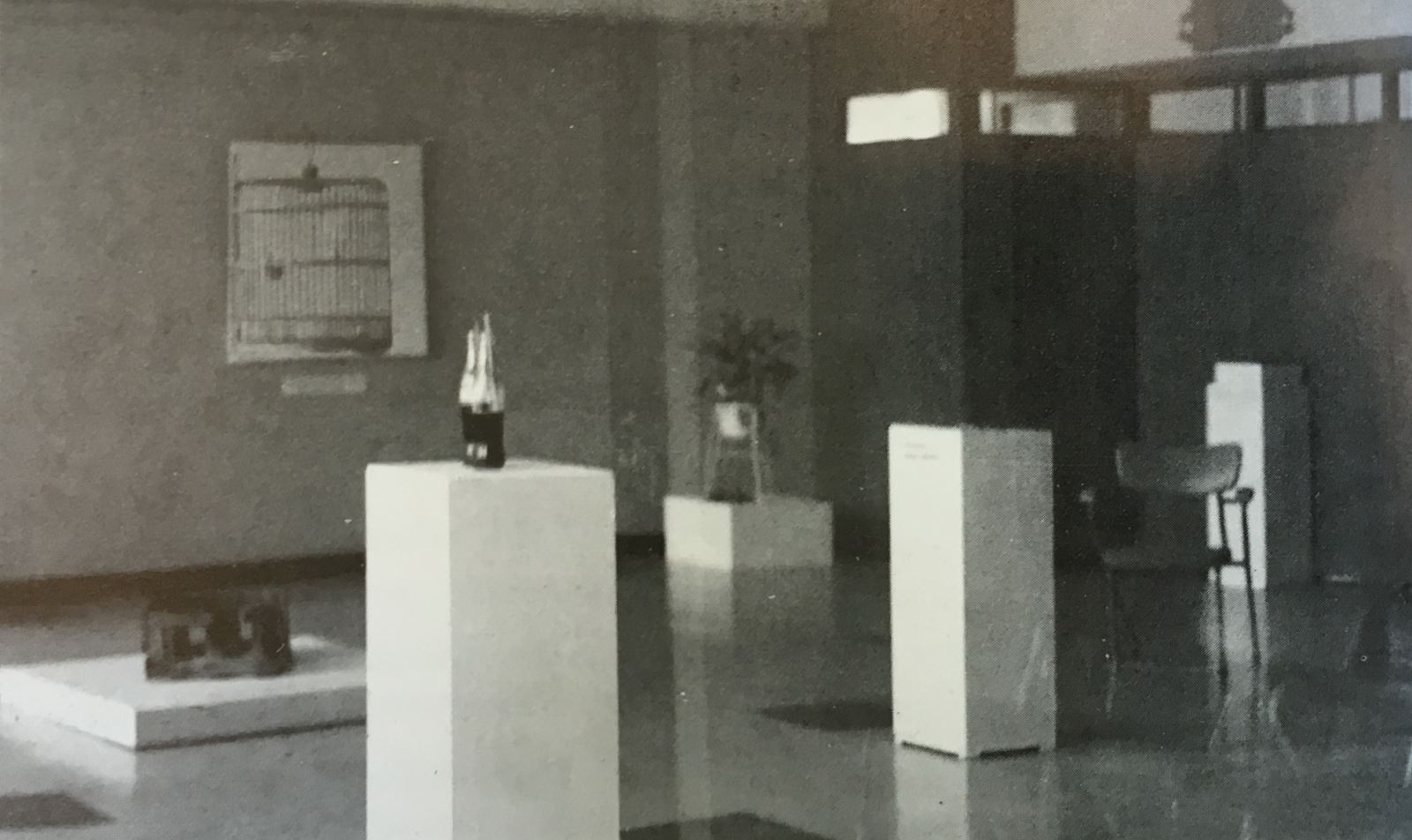

Towards a Mystical Reality exhibition (TMR, 1974)was organised by Sulaiman Esa and Redza Piyadasa who both taught at the Mara Institute of Technology (MIT, now known as Universiti Teknologi Mara) in Kuala Lumpur were not students but lecturers teaching fine art at a tertiary level. TMR shared the anti-imperialist tenor of the other critical exhibitions organised by artist collectives in Southeast Asia by producing a manifesto calling for Asian artists to “EMPHASISE THE ‘SPIRITUAL ESSENCE’ RATHER THAN THE OUTWARD FORM” as an alternative way to think about and make art that is based on a different concept of reality that is not scientific but meditative and experiential to break away from the hegemony of Western art and its art history.19 Although both Piyadasa and Esa were lecturers and not students at MIT, they were nonetheless part of the broader student movement and political environment that shifted towards art making as a socially-engaged and intellectually rigourous activity; a powerful political and cultural actor that contributed to the process of decolonisation.

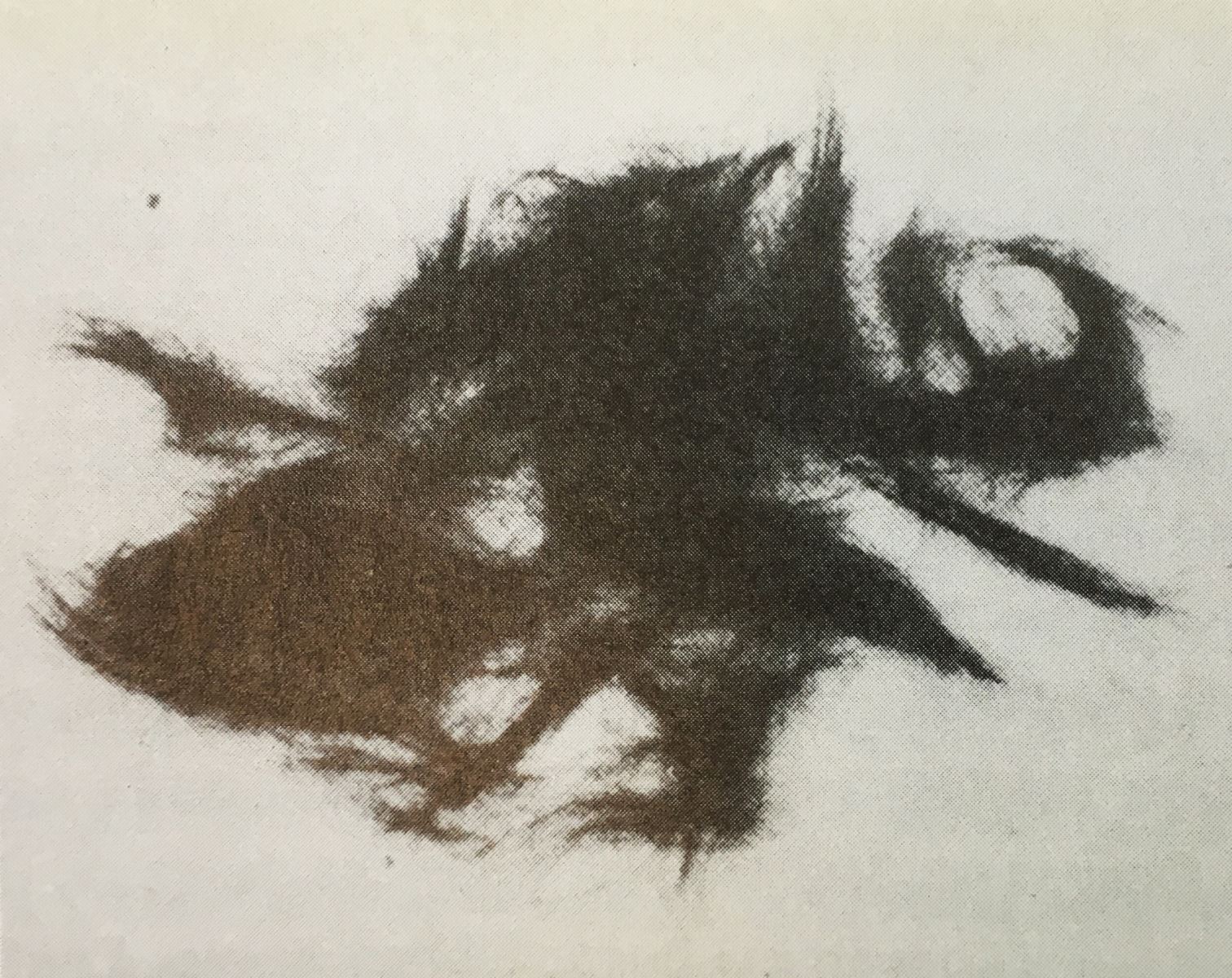

TMR sanctified ordinary daily objects, some of which like Siti’s enceng gondok was also organic material such as human hair, a live potted plant, a chair shown as it is and two Coca-Cola bottles that are half consumed (fig. 2) . Placing these everyday objects on white pedestals in a white cube gallery space immediately prompts the viewer to appreciate these everyday objects formally as sculptural artworks but draws from the Daoist philosophy of experiencing the works as events or as Krishen Jit articulates, ‘live situations’ rather than static and physical material objects. The hand-written label for “Randomly collected sample of human hair collected from a barber shop in Petaling Jaya”(fig. 3) pasted on the pedestal itself prompts the viewer to look beyond the apparent valueless and organic human hair that will be discarded as an ephemeral found object to enter a mental rather than rational space. The viewer shifts from relying on seeing and the retina with scientific observation as the framework in which to appraise the found object to being a participant who enters a ‘live situation’ using the found object as an event-centred entry point to think about who the hair came from, did this person live in Petaling Jaya and what can the hair tell us about this person. The value of the found object transform from a material and capitalist basis to one that is experiential and based on lived everyday experiences as another form of reality as stated in TMR’s manifesto that “… THERE ARE ALTERNATE WAYS OF APPROACHING REALITY AND THE WESTERN EMPIRICAL AND HUMANISTIC VIEWPOINTS ARE NOT THE ONLY VALID ONES THERE ARE.”20

Fig.2 Installation view of A Documentation of Experiences Initiated jointly by Redza Piyadasa and Suleiman Esa

Sulaiman Esa, http://www.sulaimanesa.com/works/post-london/, Sulaiman Esa Art Space, 2016, 05/05/2017

Fig.3 Randomly collected sample of human hair collected from a barber shop in Petaling Jaya

Sulaiman Esa, http://www.sulaimanesa.com/works/post-london/, Sulaiman Esa Art Space, 2016, 05/05/2017

Descending to Vulgar Images

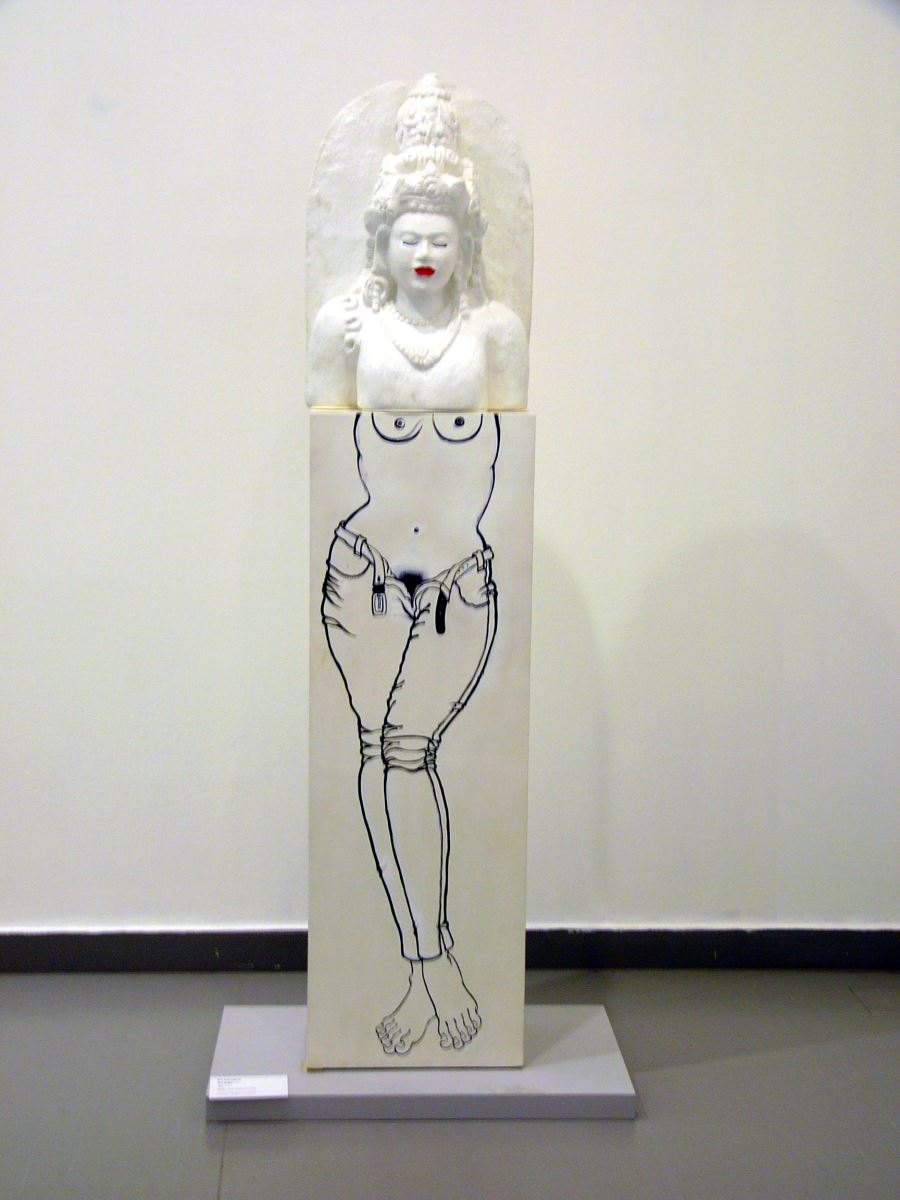

Returning to Miyakawa’s idea of Anti-Art’s return to ‘vulgar images’ to recover the fundamental structures of the everyday world, Ken Dedes (fig. 4) incited controversy when it was first shown at the New Art Movement exhibition in 1975 as it juxtaposed a cartoon-graffiti rendition of the body of Ken Dedes that was vulgar by cladding it in pair unzipped jeans revealing her pubic hair to the spectator while the head is based on the iconography of the revered Queen Ken Dedes, Queen and wife of Ken Arok who ruled the Singhasari empire in Java. It was believed that whoever married Ken Dedes would destine to kingship. Ken Dedes’ sacred powers defined by her pure beauty and sexuality are given a vulgar reinterpretation by Jim Supangkat. The meaning conveyed by the cartoon-graffiti part of Ken Dedes adopts a system of depiction based on cartoons that juxtaposes with the sculptural head that conveys a different system of representation derived from Hindu-Buddhist iconography. The combination of two different and incongruent systems of representation in one single artwork produces a new mode of representation that provokes the viewer to think critically about the differences ways in which the real was represented across time and cultural contexts.

Fig.4

Ken Dedes

Jim Supangkat

1975 remade 1996

Plastic, wood, marker pen and paint

125.5 x 41.5 x 26 cm

61 x 43.5 x 27 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Courtesy of National Gallery Singapore

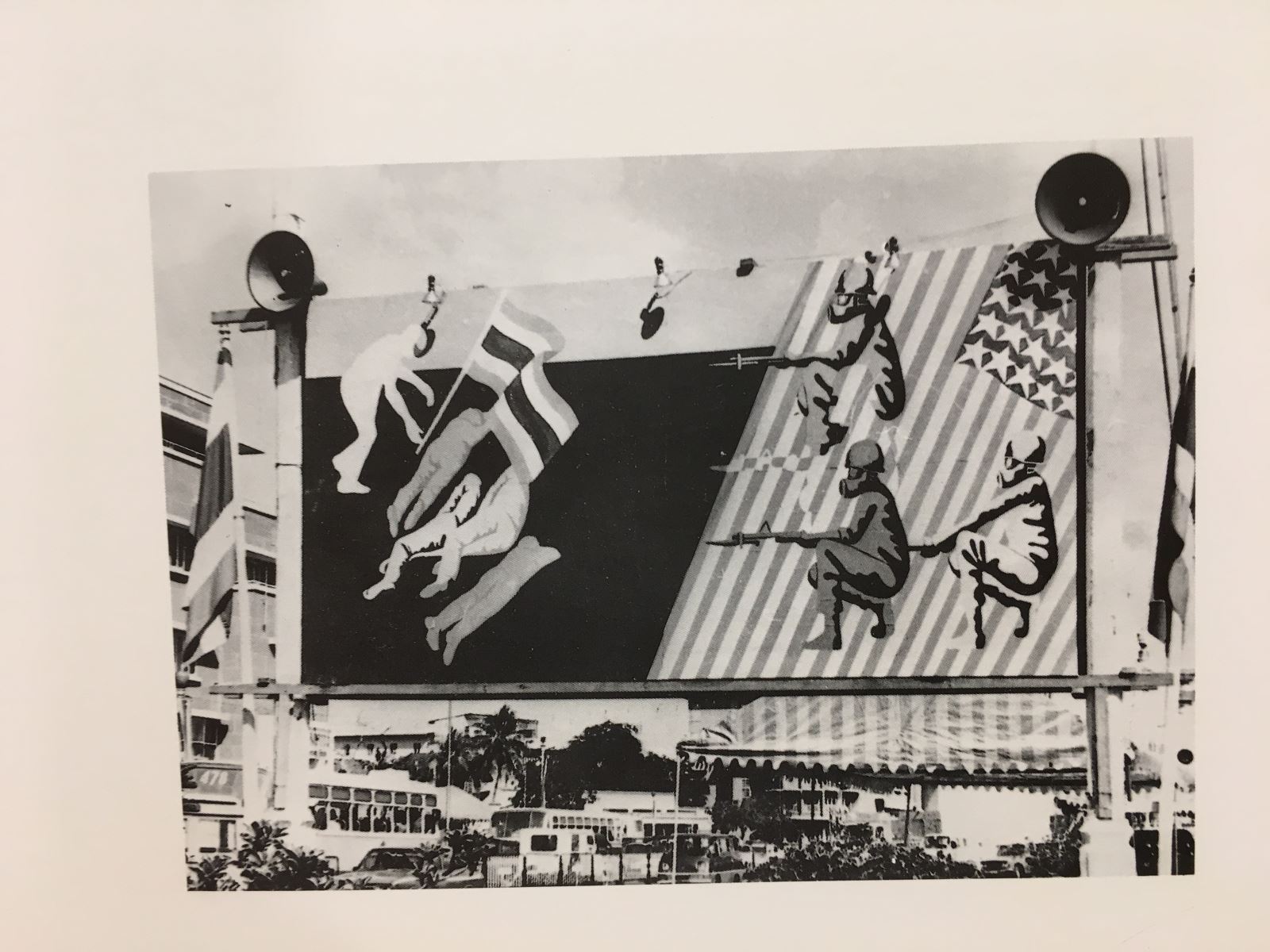

Fig.5 The Artists’ Front, Thailand exhibition of paintings, posters, murals and banners at the Rajadamnern Avenue, Bangkok

Image courtesy of Sinsawat Yodbangtoey

In 1974, The Artists’ Front of Thailand (TAFT) was formed in the immediate year after the toppling of the Thanom Kittikachorn, Praphat Charu- satien and Narong Kittikach military dictatorship in October 1973. TAFT opposed art that was for produced for capitalism controlled by those in power and big businesses and called for art to be relevant to the common Thai worker and farmer to bring culture to every Thai. Exactly one year later in Oct 1975, TAFT organised a large display of paintings on Rajadamnern Avenue with posters to commemorate the victory of the students that caused the military regime to collapse (fig. 5) . The collaboration between artists, students and ordinary Thai people to make these bill board cut outs transformed the everyday public space of Rajadamnern Avenue where the Democracy Monument – a symbol of freedom and power to the people - was where many of the student protests gathered into a site of resistance. TAFT was not alone in this as the Kaisahan similarly produced posters and murals against the Marcos regime.

Fig.6 Sinsawat Yodbangtoey from The Artists Front of Thailand beside the painting, Untitled. Image from the Author

While Ken Dedes employed vulgar images from the urban everyday, TAFT’s Untitled (fig. 6) is a bill board cut-out from its 1975 critical exhibition uses a different strategy of deploying politically charged images widely circulated in the media to awaken the consciousness of the people to the brutality and violence of the military regime. In Untitled, the image of a Thai soldier in the midst of throwing a grenade was widely circulated as through newspapers and the television. This image of the Thai soldier who is about to throw his grenade alludes to the Thai military’s violence against its own people and its participation in the Vietnam War with almost 40,000 Thai military volunteers fighting against the Viet Cong. This image captured the growing resistance against American Imperialist political intervention in Thailand to support the war effort in Vietnam. As a popular image of the war, it embodied a sense of contemporaneity in the resistance against American Imperialism, which is in action, like the grenade that is suspended momentarily in time, just about to be lobbed over the barbed wire towards the Thai national flag, the symbol of Thailand’s independence and freedom that is depicted as being wrapped around what is likely to be a coffin. The Thai national flag as the symbol of Thailand’s unity and freedom is a symbol of a universal time that does not cease if Thailand as a nation exists. The vulgarity of naked violence represented by the soldier momentarily clashes the sacredness of the Thai national flag and the golden “bowl” now painted in black, a sacred object used in Thai Buddhist and royal ceremonies to hold offerings for scared Buddhist relics that holds the 1932 Thai constitution forged from the coup of the same year. Like Ken Dedes, the vulgar of the everyday is doubly represented by the mass media image of the soldier and the violence of the military is matched by the double sacredness of the Thai people and the Thai constitution, making visible the complexities of the political and social everyday experienced by the Thai people in the 1970s under military rule.

Conclusion

Resonating with Miyakawa’s notion of ‘Anti-Art” and its descent to the everyday, the ambassador and art critic, Armando Manalo described the 1970s in the Philippines as a “period of metaphysical unrest” with the curatorial programmes at the CCP from 1971-75 as the Exposure Phase of:

Advanced art—experimental in nature—… [through] “The use of sand, junk iron, non-art materials such as raw lumber, rocks etc. were common materials for the artists’ developmental strategies. People were shocked, scared, delighted, pleased and satisfied even if their preconceived notions of art did not agree with what they encountered.21

The CCP under Raymando Albano sought to provoke audiences by making strange the familiarity of the everyday that “made one relatively aware of an environment suddenly turning visible.”22 Conceptualism in Southeast Asia was powered by the turn to the everyday centred on making visible the real was propelled by the critical exhibitions in the 1970s, producing new modes of representation that politicised the real by making it concrete, defamiliarized and even, provocatively vulgar. The turn to the everyday propelled by the critical exhibitions in the 1970s produced new modes of representation stemming discursively in notions of ‘art and life’, and the concrete; materially in the use of non-art and ‘readymade objects’; incorporating ‘vulgar’ and popular images that destabalised the boundaries between the sacred and the profane. The possibility of politicising everyday life by reclaiming the street from authorities, thereby transforming it into a collaborative display between artists, students and the public to make and install the bill board cut-outs democratised both the street as a public space and art making itself as a collective gesture. The impulsion of critical exhibitions lies in its politicisation of the everyday and in doing so, provoke and generate alternative aesthetic regimes located in reality, materiality and in the vulgar that subvert dominant ideologies and power relations.

註釋

1 Mashadi, Ahmad. “Framing the 1970s.” Telah Terbit (Out Now) Southeast Asian Contemporary Art Practices During the 1960s to 1980s. SAM, 2016. p. 13

2 Sabapathy, T.K. “Intersecting Histories Contemporary Turns in Southeast Asian Art.” Intersecting Histories Contemporary Turns in Southeast Asian Art. ADM Gallery, 2012. p. 53.

3 Iola Lenzi.“Conceptual Strategies in Southeast Asian Art: a local narrative.” Concept Context Contestation Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia. BACC, 2014. p. 22.

4 Elly Kent.‘Entanglement: Individual and Participatory Art Practice in Indonesia,’ International Convention of Asian Scholars, Chiang Mai, 22.07.2017.

5 Isabel Ching. “Tracing (Un)certain Legacies: Conceptualism in Singapore and the Philippines.” Histories Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art, edited by Say Jeffrey and Seng Yu Jin, ICAS, 2016. pp. 49-61.

6 Atsushi, Miyakawa. “Anti-Art: Descent to the Everyday.” From Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents, edited by ChongDoryun, Hayashi Michio, Kenji Kajiya and Fumihiko Sumitomo, MOMA, 2012. p. 129.

7 Ibid.

8 Highmore, Ben. “Benjamin’s Trash Aesthetics.” Everyday Life and Cultural Theory: An Introduction Routledge, 2002. pp. 60-74.

9 Please refer to Michel de Certeau, Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Randall Steven, University of California Press, 1984, on his chapter vii on ‘Walking in the City’ that illuminates on how the social practice of walking as a tactic that subjectively uses urban space, which can be extended as a form of resistance against the strategies adopted by the city planners that regulate the city. For how the everyday offers a rehabilitation of everyday life from alienation and capitalism, see Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life. Translated by Moore John, Verso, 1991.

10 Mashadi Ahmad. “Framing the 1970s.” Third Text: Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture, Special Issue, edited by Flores Patrick D. and Kee, Joan, vol. 25, issue 4, July 2011. p. 409.

11 Perez, Rodolfo P. “International Cross Currents.” The Chronicle Magazine, 5 October 1963. pp. 12-15, reprinted in Philippine Modern Art and Its Critics.

12 The Kaisahan Declaration of Principles, unpublished

13 The Artists Front of Thailand Manifesto in Building and Weaving the 20 Year Art legacy, The Artists Front of Thailand, 1974-1994, ed. Sinsawat Yodbangtoey. Con-tempus, 1994.

14 Sumartono.‘The Role of Power in Contemporary Yogyakartan Art’. pp. 23-24.

15 Sanento Yuliman.cited in Telah Terbit (Out Now) Contemporary Southeast Asian Artistic Practices During the 1960s to 1980s. SAM, 2006. p. 49.

16 Iola Lenzi. ‘Conceptual Strategies in Southeast Asian Art: A Local Narrative’ in Concept Context Contestations. p. 14.

17 The term ‘seni kontekstual’ was recorded by art historian, Amanda Rath through her interviews with F.X. Harsono, one of the leading artists of the GRSB as being used by artists associated with the Black Dexcember movement in the early 1970s. Seni Penyadaraan has been written about my Moelyono but this term was probably only used in the late 1990s specific to Moelyono’s community-based artistic practices. See Amanda K. Rath, ‘The Conditions of Possibility and the Limits of Effectiveness: The Ethical Universal in the Works of FX Harsono’, in FX Harsono Titik Nyeri/Point of Pain (Jakarta: Langgeng Icon Gallery, 2007), p. 82.

18 Email with Siti Adiyati on 1 January 2017.

19 Sulaiman Esa and Redza Piyadasa, Towards a Mystical Reality: A Documentation of Jointly Initiated Experiences by Redza Piyadasa and Suleiman Esa (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1974).

20 Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa. “Towards a Mystical Reality: A Documentation of Jointly Initiated Experiences by Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa,” republished in ed., Nur Hanim Khairudin, Beverly Yong and T.K. Sabapathy, Reactions – New Critical Strategies, Narratives in Malaysian Art. Rouge Art, 2013. p. 46.

21 Albano, Raymundo R. “Developmental Art of the Philippines.” Philippine Art Supplement, vol. 2, no. 4, 1981. p. 15.

22 Raymundo Albano. “Installations: A Case for Hangings.” Philippine Art Supplement, vol. 2, no. 1, 1981.